Superior Semicircular Canal Dehiscence (SSCD)

There are three balance canals in each inner ear. These balance canals have a membrane within them that is covered by bone. When the bone surrounding this balance membrane is missing, symptoms may appear that are very bothersome to the patient.

It has been shown in studies that approximately 2% of people have thinning of the bone around the balance canal. This thinning of the bone is thought to occur from birth as a result of poor bone deposition in the area. As the individual ages, this thin bone is worn down slowly and can even be broken down more by minor trauma to the head.

In superior canal dehiscence syndrome (SSCD), the roof of the superior semicircular canal is missing. Symptoms of this condition can include:

1) Dizziness: patients typically complain of an unsteadiness that is very hard to describe. This typically gets worse with activity or straining, such as coughing or blowing the nose. Also, exercises can make the dizziness worse. Sound, or noise, can also make patients dizzy.

2) Hearing loss: typically the hearing loss that is associated with superior canal dehiscence is a conductive hearing loss. Patients often also note that they can hear the sounds of their inner body more clearly, such as their eyes moving or sounds coming from their joints. Also, pressure in the ear and the sensation of hearing one’s own voice (autophony) may also be present.

3) Pressure sensitivity: changes in pressure within your middle ear and brain do not typically cause any symptoms. However, in this condition, changes in middle ear pressure associated with loud noise, flying in an airplane, or blowing your nose or straining, to name a few, may cause symptoms of SSCD. Because the bone over the superior canal is not present, these symptoms may occur when pressure is placed in the middle ear.

4) Hyperacusis, or oversensitivity to sound.

5) Autophony: the sound of the patients voice can be very loud in the affected ear.

6) Ringing, or tinnitus.

7) Fullness in the ear.

Diagnosis of superior canal dehiscence is made by a combination of audiometric, vestibular, and radiographic tests.

1) A hearing test will often have a typical pattern of conductive hearing loss with bone conduction scores better than air

conduction.

2) Vestibular testing may include a VEMP test, which quantifies sound sensitivity and is helpful in identifying dehiscence. Other tests may include a VNG and ECOG test.

3) Radiographic testing is very helpful. High resolution CT scans of the inner ear with reformatted images parallel and perpendicular to the plane of the balance canals is critical to diagnose this condition.

Treatment of this condition is surgical. The decision for the patient becomes whether the symptoms warrant this treatment. As this problem is an anatomical one, it will not get better on its own. However, not treating the problem will not predispose the patient to worse issues. Thus, it is a personal decision that must be made based on the severity

of symptoms.

Things that should be avoided to prevent the symptoms include:

1) lifting

2) straining

3) popping the ear

4) forceful nose blowing

5) significant air pressure changes, such as scuba diving or flying

6) loud noises and music

Surgical treatment of superior canal dehiscence includes resurfacing/ capping the superior canal or plugging the canal. These procedures can generally be performed either via a transmastoid or middle cranial fossa

approach.

The transmastoid approach involves approaching the inner ear from behind the ear through the mastoid air cells. The inner ear structure is directly visualized and the superior semicircular canal is identified. A small opening in the bone of the cranial cavity is made to allow resurfacing of the SSCD with different tissue materials.

The middle cranial fossa approach is performed by making an opening into the cranial cavity above the inner ear and mastoid cavity. The SSCD defect is clearly visualized through this approach and capping or plugging of the defect is performed from above.

These approaches are both effective in the correct patient and each have their own set of benefits and risks, that will be reviewed during your consultation.

Superior Canal Dehiscence Syndrome Case

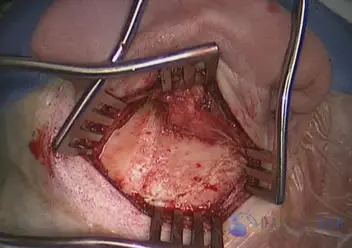

An incision is made behind the ear in the crease. This is hidden in this area so that it is not visible postoperatively. The periosteum, or soft tissue covering over the bone, is elevated to gain access to the mastoid bone.

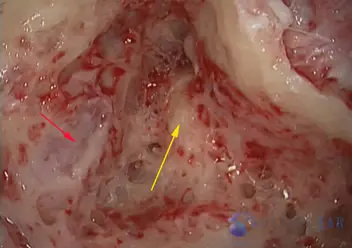

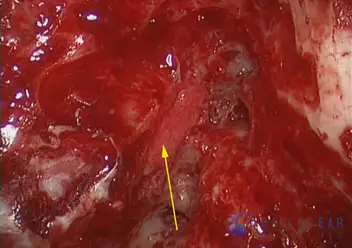

The mastoid is opened with a high speed drill utilizing both cutting and diamond burs. The wall between the ear canal and mastoid is thinned appropriately. The bony semicircular canals are exposed (yellow arrow). As can be seen in this representative case, the bone separating the dura of the brain and the mastoid cavity is often thin in patients with superior semicircular canal dehiscence (red arrow).

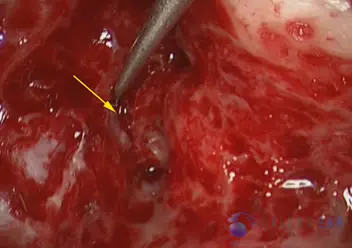

A small opening in the bone between the mastoid cavity and the brain cavity is made to gain access to the dehiscence of the superior semicircular canal (yellow arrow). This small opening is made just outside of where the semicircular canal resides.

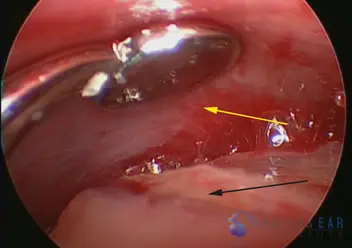

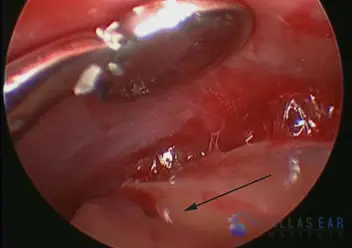

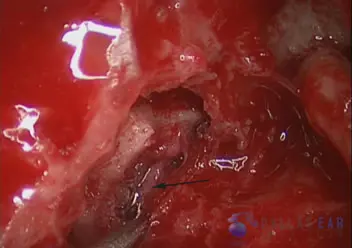

The dehiscence is clearly visualized using a micro-endoscope (black arrow). The dura is carefully elevated from the underlying semicircular canal in preparation for resurfacing (yellow arrow).

Another photo showing the bony canal dehiscence.

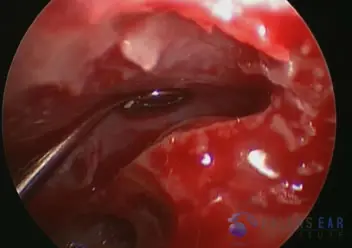

The dura is carefully elevated using an atraumatic instrument. The area of the superior semicircular canal is known because the bony canal is identified within the mastoid and location correlated.

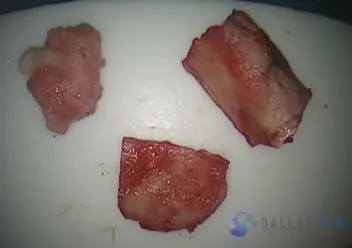

In preparation for resurfacing, the grafts are set up. A cartilage graft is harvested from the tragus, a fascial graft is taken from the temporalis fascia, and bone pate saved during drilling of the mastoid cavity.

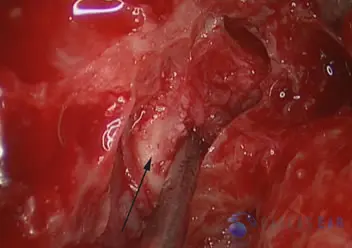

The cartilage graft is placed into the mini-craniotomy site and used as a cap over the superior semicircular canal dehiscence (black arrow).

Fascia graft is spread over the exposed superior semicircular canal and used to resurface this area (black arrow).

The resurfacing procedure is complete (yellow arrow).